Documenting Human Rights Violations - USC Spatial’s Andrew Marx and his team use smallsat algorithms to detect genocide

Can satellite imagery be used to document – and possibly prevent – genocide?

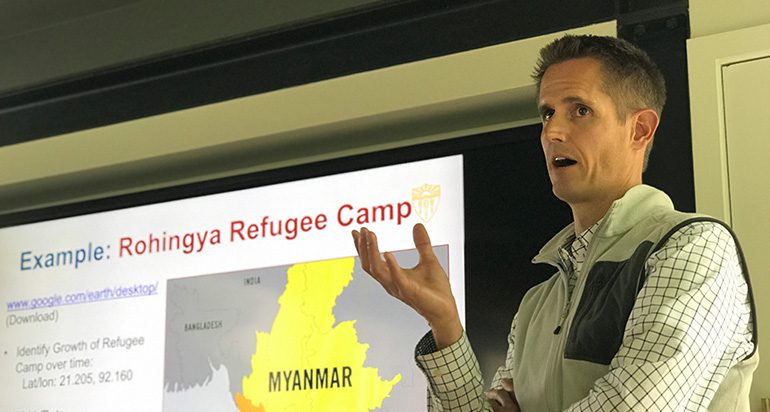

Dr. Andrew J. Marx, associate professor of the practice of spatial sciences with the USC Spatial Sciences Institute and the Institute for Creative Technologies, and his student research team are committed to developing the first human security monitoring system to do exactly that.

Marx, a recognized expert on using geospatial data collection and analysis to address human migration and refugee issues, and his team are working with Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights to developing ways in which remote sensing for GIS can document atrocities to provide evidence and corroborate refugee accounts of atrocities in international courts.

Team member Richard Windisch (B.S. GeoDesign ’18; M.S. Geographic Information Science and Technology ’19) explains, “Our current research focuses on the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar. While tensions have always been high between the minority Rohingya Muslim group and the majority Buddhist group, large-scale planned attacks by the Myanmar government began occurring in August 2017. Many of these attacks on villages included burning the villages, and eventually bulldozing them to the ground in order to have a clean slate and a lack of evidence of the village ever been there. Around the same time period in August 2017, constellations of small satellites began to provide daily imagery of the entire Earth’s surface. While too coarse to detect individual people, cars or houses can be identified. By leveraging recent developments in computer vision, time-series analysis and CyberGIS, our research project can detect and automatically alert users of human security threats such as the village burnings. So our research project goals are to develop, validate and pilot the use of smallsat technology in the first human security monitoring system that can be used by human rights organizations, NGOs and other entities seeking to corroborate on-the-ground testimonies of incidences of destruction and genocide.”

Satellite photo of Wa Peik Village, Maungdaw District, Myanmar intact

then destroyed in October 2017

“For example, a refugee talks to a reporter in a refugee camp, giving information about where she was when her village was attacked,” said Marx. “Using our current research methods, we are able to download massive quantities of images that can then be analyzed in order to provide additional evidence to the atrocities ongoing in Myanmar. Our approach seeks to use freely available imagery as a monitoring system that can alert the international community to destruction much more quickly than current methods. Currently only villages from refugees who were able to escape and give information are observed after the fact through satellite data. Our methods are proactive, covering all villages in an at-risk area, corroborating on the ground testimony.”

In July 2018, the Myanmar army published Myanmar Politics and the Tatmadaw: Part I, a denial of the Rohingya existence and ethnic cleansing against them, and the Myanmar government has continuously denied the existence of abuses. Marx said, “Satellite imagery provides data that cannot be refuted when used in conjunction with geospatial intelligence and victim testimony. We cannot stress enough the importance of refugee testimony; however, at times further evidence is required. Our methods strengthen the evidentiary power of victim accounts.”

Marx’s student team has come to appreciate the importance of their work. Said Windisch, “Prior to joining this research team, my knowledge of genocide was extremely minimal. Now, I'm understanding more about how these events occur, as well as how to leverage my technical spatial science knowledge to address them. The framework in which we approach problems allowed me to gain a holistic perspective on the material, mainly from exploring the science behind the research and the context surrounding the Rohingya from a sociocultural historic perspective. While working with the data, it can be easy to see it as just that – data. However, understanding the human components behind the data, and further relating those experiences from the refugee testimony, makes the work much more meaningful.

Team member Jong-Su Kim (B.A., International Relations ’19; M.S. Human Security and Geospatial Intelligence’20), agrees. “I learned that high-resolution satellite imagery isn't the end-all be-all of satellite imagery; coarse-resolution imagery can sometimes be more effective! I'm so used to utilizing hi-res stuff from Google Earth or Digital Globe in my studies and I've only seen media depictions of GIS utilizing extremely fine-grained imagery, so I was blind to the potential drawbacks of hi-res images when used in practical applications. I was blind, too, to the potential effectiveness of somewhat-uglier imagery.

Young-Kyung Kim, the third student research team member, is a sophomore double majoring with a B.A. International Relations and a B.S. Computational Linguistics with a minor in Human Security and Geospatial Intelligence. For her, it’s been valuable to understand what constitutes important and useful information. She said, “I've really learned how to reimagine data. Because GIS is a relatively new and growing field, finding exactly what you need is often impossible, so you have to create and analyze a lot of existing knowledge to match your specifications. Going around these constraints of availability within this project has helped me appreciate the depth and the huge amount of raw information that is already out there, waiting to be analyzed. You never know what's going to be useful next, be it social media geotags or open source data.”

The three student researchers join Marx in hoping that their research will provide proof of concept for a cost-effective monitoring tool that can be used to reduce suffering in the future. Jong-Su Kim said, “This research has really reinforced in me the belief that knowledge of and passion for such things as human rights is insufficient without a form of application. Being able to write convincingly is one form of applying this passion and making a difference and is the ‘default’ application I've been used to as an international relations major. But through my studies, I've discovered that GIS is another, sometimes more effective, way to fight for the causes I believe in.”

Young-Kyung Kim concurred. “This project really hammered home exactly why creating these tools are important in the first place. GIS can be a really technical field, but it provides a really basic understanding and perspective of human movement and patterns that can really bolster and empower decision making at every level. We want this technology to be accessible to everyone, as a part of the democratization of knowledge and the power that comes with it. Working in the lab refined and validated my career path as an interdisciplinary student! I'm grateful for the opportunity to engage a lot of different passions of mine at the same time.”

This summer, Marx spoke at the Oxford Consortium for Human Rights (OCHR) summer seminar “Human Migration, Refugee Policy, and Global Ethics” co-hosted by faculty of the Oxford Consortium for Human Rights and the Oxford Institute for Ethics, Law, and Armed Conflict (ELAC) held at Oxford University. He joined the faculty of the USC Spatial Sciences Institute in Fall 2017 as a leading scholar of remote sensing in human rights with extensive experience working with governmental and non-governmental agencies on refugee and internally displaced issues.

Read more about Marx’s research and his team’s human rights work at http://hsgilab.usc.edu/.